Recently in my neighbourhood there have been a number of car break-ins, usually where vulnerable keyless fobs have been hacked to extend the range and unlock their car. But the owners also discovered that the thieves were using signal jammers to block WiFi doorbell/security cameras. In my opinion this is a more serious issue as they are not the only devices that would be affected by this type of attack, and from what I can see on the websites of many manufacturers and vendors, these companies are not providing enough information on their smart/IoT devices to assist in mitigating this issue.

For instance, of six well-known vendors in Ireland (B&Q, Screwfix, Harvey Norman, DID Electrical, Currys, and Power City), with the exception of Screwfix, the majority of vendors of smart doorbells listed “WiFi” as connectivity, with no indication of frequency band, or other WiFi capabilities such as standard. To focus on Screwfix, while they did specify frequency band, only one of the Ring doorbells listed 5GHz, though as a “Network Standard”, not as the “Smart Frequency Band”. The rest are 2.4GHz.

On the same six vendor websites, there are other WiFi devices such as baby monitors, smart thermostats, and other home IoT devices (with little connectivity information or are again only 2.4GHz) which could also be easily affected by signal jammers that are quite easy to purchase online e.g. the DStike Deauther Watch.

Even online manufacturers/vendors also provide little to no information on the WiFi standards they use, e.g. hivehome dot com for thermostats, or SpaceSense from wizconnected dot com for smart lighting.

The broad use of 2.4GHz alone is likely because it is the most common WiFi frequency available, and has the furthest range due to its RF properties. But due to its vulnerability to interference (intentional or not), lack of channel space, and lower speeds than 5 or 6GHz WiFi, I don’t think it’s acceptable for manufacturers and/or vendors not to clearly inform their customers of their “smart” or “IoT” device’s WiFi capability, so the customer can make an informed choice and thereby future-proof their network, which is becoming more of a requirement than option, seeing how fast WiFi is improving.

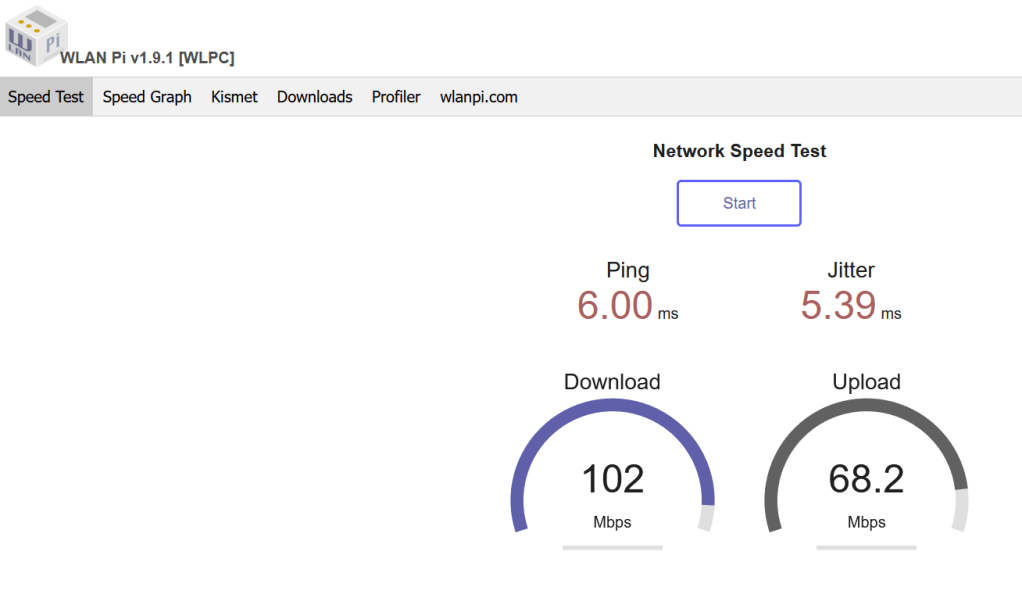

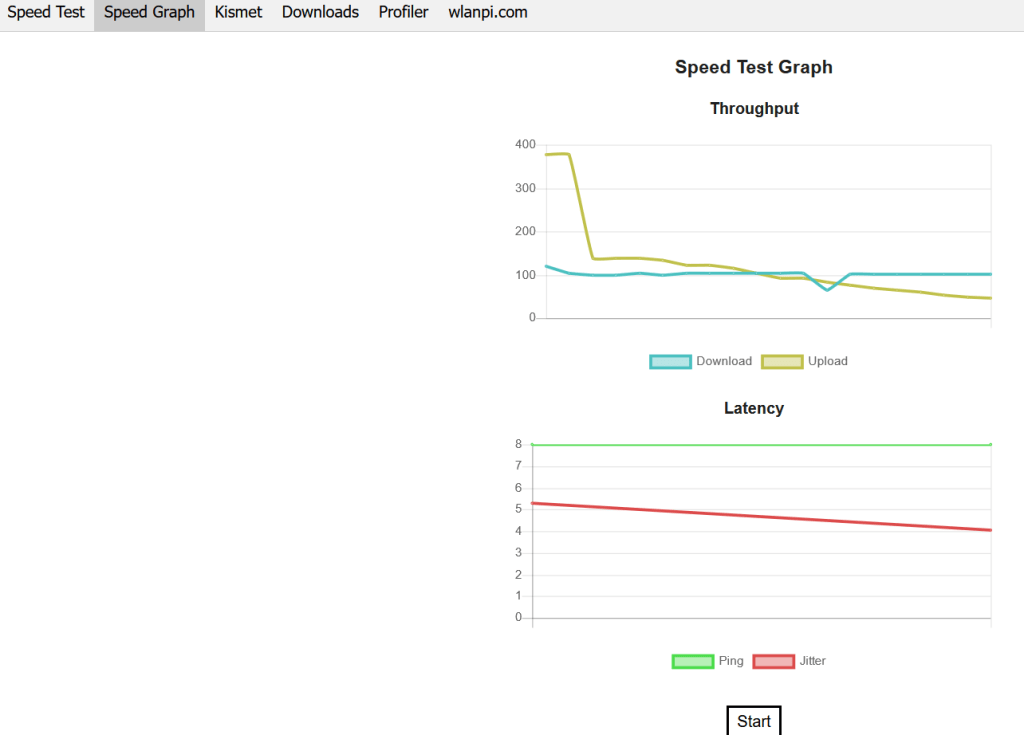

Since 2020, WiFi 6, 6E, and 7 have been introduced, utilising the 5 and 6GHz bands, with WiFi 7 having estimated speeds of up to 46Gbps. The highest theoretical speed for 2.4GHz is 600Mbps, in reality it’s closer to 450Mbps.

In Europe, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute has released 480-500MHz (5925/5945-6425MHz) of the 6GHz spectrum for unlicensed systems, while the Federal Communications Commission in the US has opened up the full 1200MHz, i.e. 5.925–7.125GHz. While users in Europe arguably still need more spectrum in 6GHz, I hope that more awareness of the IoT focused security features of WPA3 such as Easy Connect, and more choice of 5GHz and 6GHz WiFi products will result in WiFi manufacturers and vendors providing better service to their customers, and that smart/IoT home and enterprise networks will benefit significantly from these updates, not least at layer 1.